Blog 8 - Favourite places 3 - Old Growth Forest section of the Walpole-Nornalup National Park

Walpole-Nornalup National Park has a special 'place' for many people in Western Australia. It contains significant stands of the largest trees in WA - Karris and Tingles - and the parts of the park with Old Growth trees are of special value. The Park has several car parks and associated short walking trails that enable visitors to walk among the trees. As well, the Bibbulmun Track runs through the Park (The Bibbulmun Track is one of the world’s great long distance walk trails, stretching 1000km from Kalamunda in the Perth Hills, to Albany on the south coast - link to website). The large number of visitors to the park, the many walkers who walk the Bibbulmun Track, and the importance that even non users and visitors attached to the Park means this is a 'place' not a 'space'.

There is also a Tree Top Walk that allows people to walk through the canopies of Karris and Tingles - Valley of the Giants - see below - (link to the website).

Tree Top Walk through karri and Tingle trees

There is a section of the Bibbulmun Track north and east of Walpole that passes through the old growth section of the Park, which I have walked several times, and I never cease to be in awe of this forest.

Below is a collection of photographs from the last time I walked this track. I hope you get at least a small sense of what it’s like to walk through this place.

Garry Middle, December 2024.

Blog 7 – Favourite spaces and places 2 – Outside Amsterdam train station

My next favourite pace is the public space outside Amsterdam train station.

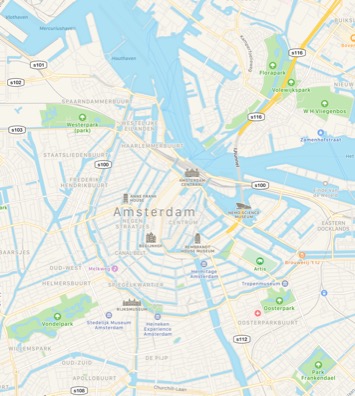

Figure 1 below shows the location, and Figure 2 is a Google Earth view. Figure 3 shows the main entrance to the train station.

Fig 1: Amsterdam train station and outside public space - location

Fig 2: Aerial photo

Fig 3: Main entrance to the train station

As can be seen from the aerial, the open space in front of the station is dominated by pedestrians, and the only vehicles allowed in are trams (Figure 4) (other than service vehicles) – this is the most important terminus stop for trams in Amsterdam. As can also be seen, the canal adjacent to the open space is where all the tourist ferries leave from (See also Figure 5).

A quick note about the photos below – I deliberately took these with as slow a shutter speed as I could manage. As a result, what each photo shows are the varying movement and non-movement patterns at the open space, which helps describe what goes on here.

Fig 4: Trams terminus

Fig 5: Tourist ferries’ boarding area

I will argue here that this open space acts like a paired down Town Square – i.e. it is a public place - although I don’t think it was designed to be this. I visited this place a number of times on my visit to Amsterdam, and I really enjoyed just standing there and watching all that was going on. It’s not much to look at – it’s just a paved area with lots of people and trams – but there was a lot of positive energy about the place. It was fun just to be there. Although I should note that the train station itself is a significant and iconic building (see the selfies in Figure 3), but it is a backdrop to the place not really part of it.

I think that sometimes we can over think, over plan and over organise a space and it ends up feeling contrived. There is a sense that it belongs to the designers and organisers and not the users. Amsterdam Central open space is not one of these. It has become ‘place’ because of its location and public transport infrastructure within it and adjacent to it. Other than that, it has not been planned but it was evolved.

In noted in an earlier blog that

… Town squares are often the main public places in major cities or towns where people congregate during the day, and where major events are held. They are typically located within the commercial/retail/business heart of the city, and usually there are few people who actually live nearby and who would call this place ‘local’. These places have many regular users who come from all over the city, who work in the city area. Other visitors are regular shoppers, tourists, or people who regularly/occasionally attend events held in the square. In these ways, these squares are ‘owned’ by the whole city.

It’s certainly true that people do congregate here (Figure 6), although unlike typical Town Squares, there are no facilities that allow people to stay for an extended period of time – seats etc. In general people gather here because it is a well-known and easy to access location (pubic transport). It’s a meeting place for locals meeting up to then going on to their main destination or activity, and for tourists to either catch a ferry, a tour bus or public transport (Figure 7). There is a strong sense of ownership about this place, and it is generally ‘known’ by locals and tourists.

Given it’s a significant meeting place, people may well have strong memories about meeting up with friends, people they haven’t seen for some time or the start of an enjoyable tour or night out.

Whilst formal events aren’t held here, these meetings can be seen as ‘mini events’ in people’s lives (Figure 8).

Fig 6: Meeting up

Fig 7: Tourist groups gathering

Fig 8: Various activities happening

I particularly like this last photo as it shows the full range of what people do here – people in a hurry, people walking more slowly and chatting, individuals waiting for someone including ringing them to find where they are, someone who has just arrived from somewhere not local and have met their friend, an organised group (in front of a banner) and a group having a quick bite to eat.

If I was to use a single argument about why this is a ‘place’ and not a ‘space’ it would be that, as a meeting place, it creates memories for many who meet here, memories attached to the people and the place.

Garry Middle March 2018

Blog 6 – Favourite spaces and places 1

Forrest Place, Perth Western Australia

With the ‘theory’ out of the way, I’ll now turn to the fun part – my favourites spaces and places. In each blog, I will select a ‘favourite’ example of one of the types of spaces and places I have defined in previous blogs. I use the word ‘favourite’ in both a positive and negative sense. I’ll describe places/spaces that I really like and enjoy, or have enjoyed, visiting. I will also give examples that are highlight some of the worst elements of design or highlight other problems.

I’ll begin with a Town square – Forrest Place in the centre of Perth. This is definitely the most significant public place in the Perth CBD

Fig 1 shows its location and Fig 2 is a recent Apple Maps aerial of it. Fig 3 is a view of Forrest Place from the southern end looking north.

Forrest Place is strategically located in the heart of the city and its retail sector, and between both the central trains stations. Its acts as both a location (place) and a transit space, especially to access the two central train stations.

Fig 1: Forrest Place - location

Fig 1: Location Map

Fig 2: Aerial photo of Forrest Place

Fig 3: Forrest Place – view from southern end looking north

The key piece of infrastructure is the Jepp Hein fountain, which is the cross hatched area visible in the Fig 2, and visible in the middle ground of Fig 3. The fountain is designed to have an irregular water ‘spurting’ sequence, which makes is unpredictable as to when it will come on and how high the fountain water will be in a particular section – Figs 4-7 below show people interact with the fountain.

Figs 4 - 7: Different human interactions with the Jepp Hein fountain

As can be seen, it is a particular attraction for children, especially during the summer months. I have seen instances where families arrive in the Place, the kids are automatically attracted to the fountain, they begin to play with the water, first by trying to dodge the jets of water, but then, inevitably, they get a bit wet, and eventually a whole lot wet. Many parents come unprepared, and a quick trip to the Myer department store on the eastern side of the Place is needed to buy towels and dry clothes!

The City provides temporary shade and deck chairs, mostly for the adults to use.

Figs 8, 9: Shade and deck chairs in Forrest Place

All of this human interaction is itself a feature, and many people sit or stand on the fringes of the fountain just to observe these interactions – Fig 10.

Fig 10: Observing the ‘fun in the fountain’.

Forrest Place is a popular at lunchtime, with many people – shoppers and those working in the City - using the chairs and tables provide to eat their lunches, or simply just to sit and rest.

Figs 11, 12: Lunch time at Forrest Place

Figs 13, 14: Just siting and relaxing in Forrest Place

The section nearest the main Perth train station (north side) has a grassed area, a stage – both popular for sitting and relaxing - and an unusual piece of art colloquially known as the cactus. Very few people take much notice of it, and it appears to be largely a landmark and a place to meet up.

Figs 15, 16: Northern end of Forrest Place and the Cactus

This end is also popular as a meeting place for groups of young people, especially away from the areas used by families and diners – Fig 15, and the north west corner shown in Fig 17.

Fig 17: Forrest Place meeting spot for groups of young people

The southern section is well shaded with several mature trees, and there is a café which has been allocated some of the Place for its diners – effectively an acquired non-space, or commercialise private space.

Fig 18: The café in Forrest Place

Fig 19: The acquired non-space

Just to the west of this private dining area is a piece of interactive art – a large granite ball supported by a fountain – Fig 20. The fountain makes it easy to make the ball roll and turn.

Fig 20: Interactive granite ball

The history of the Place is interesting. As with many public places in inner city areas, Forrest Place was originally a street, but was closed to traffic and paved as a public mall in 1986.

Fig 21: Forrest Place before its closure - https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/Forrest_Place_1971_.tiff/lossy-page1-220px-Forrest_Place_1971_.tiff.jpg

For many years Forrest Place remained relatively undeveloped as the poor quality aerial photo below shows.

Fig 22: Forrest Place in 2005

I was advised by one of the City of Perth officers who worked on a re-development master plan for Forrest Place in 2008, that there were several driving forces behind the push to re-development it:

- The retailers – especially Myers – saw a re-development as being good for business;

- There was an emerging place making movement in Perth pushing for better public places; and

- Safety concerns.

This last driver is interesting. Up until its re-development, Forrest Place was a meeting place for several disadvantaged and minority groups – homeless men, Indigenous groups, Emos/gothics and groups of teenagers. Workers going to and from the train station – often women - and shoppers reported to the City of Perth they felt unsafe using Forrest Place because of the presence of these groups. Also, the behaviour of these groups made for an unpleasant atmosphere.

By activating Forrest Place, more people were drawn to it, which inevitably caused the disadvantaged and minority groups to leave Forrest Place and find other locations. This is probably an intended consequence of the place activation, but I can find no evidence that as part of the re-development, the needs of these groups were taken into account – it seems it was just assumed they would find other spaces to go to.

It raises the interesting question as to what rights do existing users have when a public space is activated, a process that will inevitably impact on those existing rights as new users are drawn to the space. Forrest Place is a good example of this planning dilemma.

There is no doubt that the existing Forrest Place is a significant ‘public place’, which I defined in my first blog as one which “… is owned publicly, has regular users who have a certain sense of ownership and private geography. Social interactions are common here.” The notion of private geography is strongly related to ‘sense of place where I noted in my first blog “… the regular users of the place, who have a sense of ownership and responsibility for it and a certain sense of “private geography” will emerge.”

The regular users are those who work in the city and regular shoppers. The impact of the fountain is significant in building the sense of place and ownership, as many people will have happy memories of their visit to Forrest place because of their direct interactions with the fountain or their observations of other people’s interactions. I haven’t mentioned this before, but memories are a critical element in defining sense of place. I may explore this some more in a later blog.

But, this is a different sense of place than was present before the re-development. There is little doubt that the previous users had developed a sense of ownership, but this has now been replaced with a different sense of place. It’s fair to say that it would be very difficult for the new sense of place to embrace the old one.

Whilst I think this issue is important and one very underdone when space activation occurs, I don’t want to distract from how successful Forrest place is as a public place. As well as all the features noted above about its design and how it is used, it also has the additional feature typical of most Town Squares - Forrest Place is also used for events, including Friday night markets and concerts.

It is one of my favourite places in Perth.

Garry Middle January 2018

Blog 5 – Categories of Public non-spaces

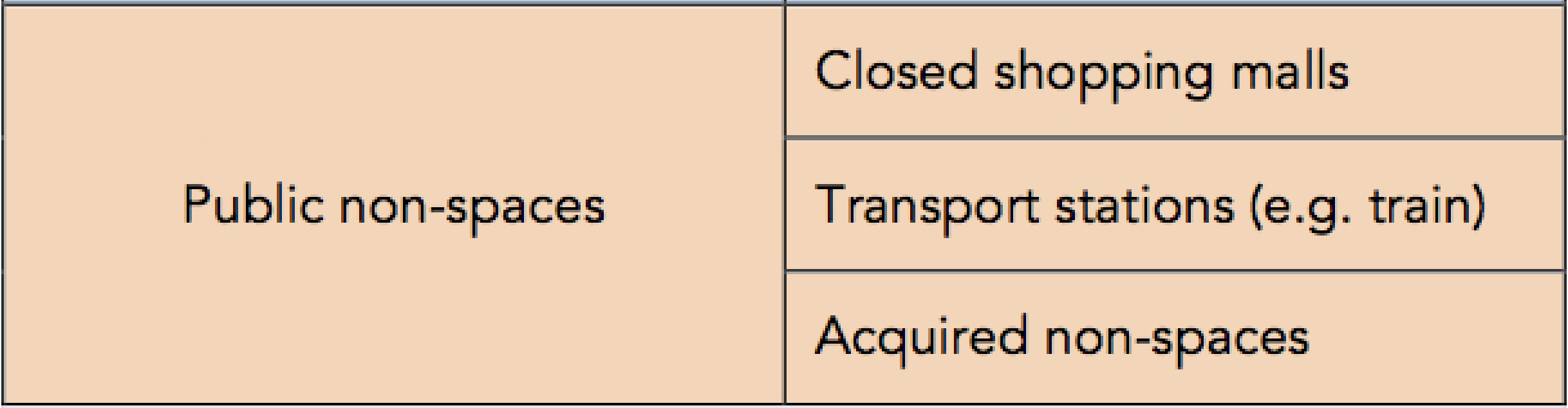

Below is the figure showing my categories of public non-spaces:

As noted in my first blog, a public non-place – which is generally privately owned - is created for people who want to use the primary service of the owner, and this space is somewhere to wait or pass through. These places have little sense of ownership by the users, and favour solitary behaviour over social interactions.

Please note that all photographs are taken my me, unless otherwise attributed (e.g. from Google Earth).

Close shopping centres

The primary purpose for visiting these shopping centres (called shopping malls in some countries) is for the purchase of goods and services. The typical overall design involves having a main building surrounded by a large parking lot, meaning that the main access is via car. This design has been modified in recent years (see below) but this main design still dominates.

Importantly, it’s the inside of the main building that act as public space. Access to these buildings is controlled by the centre owner/manager, with opening hours strictly controlled. The majority of the retail outlets in the centre can only be accessed from inside the centre, although outlets with extended trading needs, for example pharmacies, are situated near entrances and have access to them from both the outside and inside.

The design of the internal space is what is of interest here. In general, it consists of one, or a few, wide spaces connected to the entry points by narrower transit ways. The wider spaces are generally food halls (Fig 1), which is where people tend to stop and where the social interaction occur. The transit-ways are primarily for walking (Fig 2), although there is occasional seating and quieter spaces provided where people can rest (Fig 3).

Fig 1: A food hall

Fig 1: A food hall

These transitways often have small kiosk-type retail outlet or pop-up stalls (Fig 4)

Fig 3: Quite resting space within a transitway

Fig 4: Small kiosk within a transit way

As these spaces are privately owned, access to them tightly regulated, and behaviour also tightly controlled through the use of security guards, there is generally a lack of sense of place in shopping centres. The owner also controls the design of the space, with little, if any, consultation with the users: people are seen as customers rather than users and the internal spaces are designed to encourage shopping.

For the most part, visits to shopping centres are seen as functional – i.e. for shopping – although, as mentioned above, food-halls and cafes offer the opportunity for socialising. However, in extreme weather events – heat waves and cold snaps – people may choose to visit shopping centres purely for social reasons as shopping centres have climate control and offer relief from the extreme weather.

In summary, shopping centres are highly regulated privately owned spaces that are popular destinations for people to primarily carry out shopping, but some of the internal spaces and retail outlets allow for limited socialising. There is generally a very limited sense of place that develop in these spaces.

It’s worth noting that in some cases, shopping centres are adding a ‘main street’ retail strips, which are open areas and with two rows of retail outlets either side of a road (Figs 5 and 6). These retails outlets are often food related and operate for much longer trading hours than the shops within the centre proper. The road is accessible all the time, so, in effect, these operate as open malls – see previous post.

Fig 5: Aerial view of Rockingham City Shopping Centre with added on ‘main street’ in the north east corner

Fig 6: Street view of Rockingham City Shopping Centre ‘main street’

Transport Stations

Like shopping centres, these spaces are privately owned and highly functional – they are spaces for people to wait to either catch a train or bus, or to wait for someone to arrive. Typically, they are large enclosed spaces – for example Fig 7, which is the Florence train station.

Fig 7: Florence train station

The transport stations that attract large numbers of people, often have retail outlets, especially fast food, within them – Fig 8.

Fig 8: Copenhagen train station with a Macdonald’s

As with shopping centres, there is generally a lack of sense of place that develops in transport stations, even though there are many visitors.

Notwithstanding this, these stations, especially train stations, are often important, well known and easy to get to locations, and the open space areas in the front of the stations become important meeting places – Figs 9 and 10.

Fig 9: Open space in front of the Central train station in Amsterdam – a popular meeting place

Fig 10: The wide footpath in front of the Flinders Street train station in Melbourne – also a popular meeting place

I have used the word ‘place’ here very deliberately as this community acceptance that these spaces are for meeting creates a real sense of place – a ‘meeting’ sense of place. They are equivalent to Town Squares (Amsterdam) or streets (the footpath in front of the Flinders Street train station).

Acquired non-spaces

These are, in effect, locations within an otherwise public space that have become privatised or commercialised. Typically, these are areas of public footpaths adjacent to cafés and restaurants that are used for out-door dining. In effect, to get access to these locations visitors have to pay (i.e. order food and/or drinks), and the non-paying public is excluded (Figs 11 and 12).

Figs 11 and 12: Acquired non-spaces on footpaths for paid outdoor dining

Areas of town squares and other public parks are also acquired in this way - Fig 13 and 14 – with the worst example if have seen is in Dordrecht in Holland where the only remaining un-acquired space is a walkway – Fig 15.

Figs 13 and 14: Acquired spaces in town squares and other public parks (Porto and the foreshore in Esperance, WA)

Figs 15: Merge photo showing a Town square in Dordrecht that is almost completed acquired for out door dining

Another example of acquired space is when private land owners adjacent to public open spaces place their private infrastructure within the space and use it for their own private purposes – Figs 17 and 18.

Fig 17: A resident using the adjacent public reserve to locate play equipment (Bunbury WA)

Fig 18: Boats creating an acquired space by being stored within a public foreshore in Lake Macquarie, NSW

In some cases, land owners remove the fence which delineates the public/private boundary making the acquiring process more subtle and difficult to detect – Fig 19.

Fig 19: Residences adjacent to a foreshore Reserve in Smithton Tasmania and one property owner removing the property boundary fence, effectively acquiring a portion of the public reserve

In summary, acquired non-spaces are areas within public open space that have become privatised for either commercial or private use, effectively excluding the broader public.

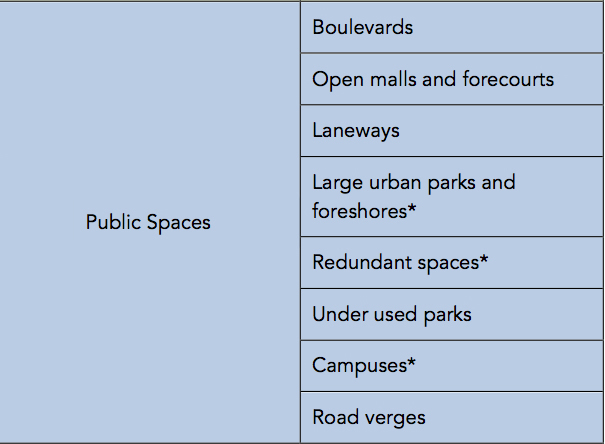

Blog 4 – Categories of Public Spaces

Below is the figure showing my categories of Public Spaces.

* Parts of some of these large can emerge as claimed places and coastal and foreshore nodes are generally planned to be places within broader foreshore spaces.

As noted in by first blog, public spaces are typified by being frequently used by passer-byer’s who don’t really have a sense of ownership and there is a very weak sense of private geography.

Please note that all photographs are taken by me, unless otherwise attributed.

Boulevards

I’ll start with a quote from the Green Day song “Boulevard of Broken Dreams"

“I walk a lonely road

The only one that I have ever known

Don't know where it goes

But it's home to me and I walk alone

I walk this empty street

On the Boulevard of Broken Dreams

Where the city sleeps

And I'm the only one and I walk alone”

Modern boulevards may best be described as ‘unlonely’ streets where pedestrians dominate and the adjacent land uses are both destinations and aesthetic attractions. The primary purpose of the pedestrian-way is to allow transit rather than being places to stop and do things. The adjacent land uses are what draws people to the boulevard, and both length and variety add to the attractions.

Many boulevards run along foreshores with the water body a significant aesthetic attraction (Figures 1 and 2). Others run through the middle of the city and may have open space (parks) adjacent to the pedestrian way (Figure 3 and 4).

Fig 1: Popular water front boulevard in Porto, Portugal

Fig 2: Barangaroo Headland Park, Sydney Harbour.

Fig 3: Boulevard in the middle of Athens

Fig 4: View of the Washington Mall

Some boulevards have commercial land adjacent to the pedestrian-way – for example cafes, galleries and other tourism related businesses (Figures 5 and 6).

Fig 5: Darling Harbour (Sydney) at night showing the various cafes adjacent to the pedestrian way

Fig 6: Southbank in Melbourne

Walking is the most popular activity, but in the early mornings and late afternoons, running, cycling and other fitness activities are popular (Figures 7 and 8).

Fig 7: Early morning runner on the circular boulevard in Lucca Italy

Fig 8: Early morning exercisers, Swan River Perth.

Whilst these boulevards attract a lot of people, many are occasional users and tourists, which makes the development of sense of place less likely.

In summary, boulevards are popular long pedestrian ways, with limited senses of place, that allow transit and exercising rather than being places to stop and do things, with the adjacent land uses, often including linear waterways, cafes and parklands, drawing people to the boulevard.

Open malls and forecourts

I have grouped these two together because there are strong commercial motivations around the creation of these spaces.

In some ways, open malls are short versions of boulevards. They are typically closed off roads with retail shopping outlets on both sides. The primary purpose of these spaces is to attract people and to enhance the shopping experience (Figures 9 and 10).

Fig 9: Rundle Mall in Adelaide

Fig 10: Burke St mall, Melbourne

Most malls have infrastructure that add to the aesthetics and usability of the space which encourage users to spend time in the mall, for example seating (Figure 11) or public art (Figure 12).

Fig 11: Playground in Manly shopping mall

Fig 12: Public art in the Launceston shopping mall

These spaces are generally popular, but most people stay for only short periods of time, and the regular visitors are those who work in the city.

Forecourts are generally created in the front of large buildings and are technically private spaces –i.e. within private property - but they are permanently open to the public. The owners often create rules about how the space can be used (Figure 13). This sense of private control works against any sense of place developing. Because these are private spaces, the owner can hold their own events – Figure 14 shows a statue of Marilyn Monroe temporarily located in the forecourt of a tower in Chicago

Fig 13: Central Park tower forecourt in Perth, with a sign displaying the ‘rules’ of entry

Fig 14: A statue of Marilyn Monroe temporarily located in the forecourt of a tower in Chicago

In summary, open malls and forecourts are created spaces with a strong commercial basis for their existence – either in support of retail shopping or as publicly available but privately regulated spaces within the boundary of a large building. This primary, non-public, purpose for these spaces works against the development of any sense of place despite their popularity.

Laneways

These are public spaces in that they are, or were, roads. They tend to be narrow and function as pedestrian ways as well as for cars. In some of the older parts of cities like Perth, lanes were used to service houses, for example, the removal of human waste. Figure 15 below shows and old back lane in North Perth. Many laneways in city CBDs have been converted into commercial areas, mostly with cafes and street dining (Figure 16), in part in response to safety concerns – increasing human activity increases surveillance and reduces the safety risk.

Fig: 15: Back lane in North Perth

Fig 16: Commercialized laneway in Christchurch, New Zealand – in this case outdoor seating for a small pub

The undeveloped laneways are primarily about pedestrian movement from one location to another, often being short cuts, and have very limited senses of place. The commercialized laneways, whilst being much more interesting spaces, and more popular transit-ways and destinations, become destinations by acquiring public space and making it private – I have called these’ acquired non-places’, and I discuss these in detail in my next blog.

In summary, laneways are narrow roads, often found in the older parts of cities, whose primary purpose is as pedestrian transit-way, and many CBD laneways have become developed for commercial purposes, thus increasing their popularity and becoming destination spaces as well.

Large Urban Parks and foreshores

These are the large pieces of open space that are largely undeveloped, have low visitor numbers, and usually have a specific purpose not necessarily supporting place making. As noted in my previous blog, certain high user areas within these spaces, usually with supporting infrastructure, can be become acquired places – for example coastal nodes. In WA, we are lucky that the coast – the beach and nearby foreshore areas – are contained within public reserves. Certain locations within these reserves are developed as coastal nodes with the remainder largely remaining undeveloped. These undeveloped areas are mostly fenced off to protect the vegetation, and usually have paths and formal tracks that go through them to allow pedestrian and cycling access (Figure 17). In other locations, the foreshore is narrower with little, if any, vegetation, and the surrounding land uses are residential and open space (Figure 18).

Fig 17: Path in the coastal foreshore between Coogee and Woodman Point south of Perth

Fig 18: Foreshore in Brighton, near Adelaide

The beach is accessible to the public.

Thus, the primary purpose of these areas is conservation or open space, with supporting passive recreation. In some sense, these foreshore areas are like passive boulevards with the land uses adjacent to the path being conservation, open space and/or residential, and the land uses adjacent to the beach are conservation or open space, and the ocean.

Large urban bushland reserves have the same qualities, without the ocean as an adjacent land use (Figure 19). Many large, poorly designed town squares and large inner city parks also come under this category as they simply serve as a pedestrian transit-ways or have poor visitation rates (Figure 20).

Fig 19: Kings Park in Perth

Fig 20: City park in Darwin

There is an argument that some of these places can develop a clear sense of place, exactly because they are not well visited, as they have a sense of wilderness, or people feel a sense of aloneness. This is particularly true of some urban beaches (Figure 21). I will stick my neck out here and say that this sense of personal aloneness is about the space being acquired for a private, not public, use. The sense of place is, therefore, an acquired private sense of place and not a shared public sense of place. Similar to isolated beaches, people can find locations within large, not well used, town squares and city parks for quiet contemplation and to find a sense of aloneness (Figure 22).

Fig 21: Someone finding a sense of wilderness or feeling a sense of aloneness on an isolated urban beach

Fig 22: Someone finding a feeling a sense of aloneness in a large urban park in Porto, Portugal

In summary, large urban parks and foreshores are large spaces with low relatively visitation rates whose primary purpose is other than providing opportunities for place-making. They have features (beaches) of infrastructure (paths) that allow for pedestrian transit, but little opportunity is created for developing a public sense of place, although remote locations within these spaces may allow for an acquired private sense of place associated with aloneness to develop.

Redundant spaces

Redundant spaces are simply those spaces that are neglected, left undeveloped and have little, if any, function. A power line easements is one such space (Figure 23), and another are awkward pieces of green space created when road alignments are changed at intersections (Figure 24)

Fig 23: Powerline easement

Fig 24: Green space created in the front of houses when the road was realigned furrier away from the houses

Some medium strips fall under this category as well (Figure 25). In some cases, these spaces evolve through changing urban and street design where roads and paths become unused as new construction blocks the flow of the path (Figure 26).

Fig 25: Largely functionless medium strip in Leura

Fig 26: A road in Lucca Italy that has been blocked and is now redundant

Under used parks

These are small to medium sized parks that, well, let’s be frank, are poorly designed, do not meet the needs of potential users, and are underused. They are can be those designed and built by developers to ‘market’ the development to a particular demographic – for example young families – but the suburb has outgrown that design (Figure 27). They can also be too small for any practical use with few if any infrastructure (Figure 28)

Fig 27: Underused park in Dunsborough WA. Well designed but not suited to the demographic of the suburb

Fig 28: Small park in South Fremantle with no useable infrastructure

Campuses

These are large tertiary institutions that are too large to be fence off and access controlled, and the main population that accesses them are students. Their grounds and open spaces can be extensive, but there is both a ‘privateness’ and ‘temporariness’ about them (Figure 29). Any member of the public can access these spaces, but it is largely not encouraged and, thus, the sense of ‘privateness’. The key users are, for the most part, only there for short periods of time, and, whilst some sense of place may develop, it is soon lost once students graduate. Some of the spaces and courtyards of buildings and have a stronger sense of ‘privateness’ (Figure 30).

Fig 29: TAFE campus in Adelaide

Fig 30: More private open space in Sydney University

Interestingly, some universities are putting a lot of effort into landscaping an adding infrastructure, with the aim of creating a stronger sense of place so as to encourage students to be on campus more often and longer (Figure 31).

Fig 31: Hammocks provided at Curtin University as a way to add to the sense of place

Road verges

A road verge is different from a street verge in that sense of place develops in streets verges because pedestrians stop and spend time in the street, whereas a road verge is simply a pedestrian transit way. Figures 28 and 29 in my last blog shows the differences between a street and road verge – shown below as Figures 32 and 33.

Fig 32: A typical neighbourhood street showing good connections between the house and the verge and the presence of a footpath – a street verge

Fig 33: A verge in a different neighbourhood with poor connection between the house and the verge and the absence of a footpath – a road verge

Below are some more examples of road verges.

Fig: 34: Narrow road verge – the Causeway in Perth

Fig 35: Road verge in inner Brisbane

Fig: 36: Road verge in Chicago

Fig 36: Very narrow road verge in Florence

Categories of Public Places

Below is the figure showing my categories of Public Places.

Please note that all photographs are taken by me, unless otherwise attributed.

As noted in by first blog, Public Places are typified by having regular users who have built a sense of ownership for the place through frequent social interactions.

Neighbourhood parks

These are small local parks that are well designed, used primarily by locals, and have a range of facilities, often including playground equipment. Both design and location are critical in these sites becoming public places. They are generally located in residential areas, either low density suburbs or adjacent to medium and higher density nodes. In the later cases, these places are highly significant and are likely to have higher useage in part because of the greater number of people with the place’s catchment, but also because they compensate for the absence of backyards present in low density suburbs. See below for examples. These places have a strong sense of local ownership.

The park on the left is in a low density suburb of Perth, whereas the second in inner city Geneva.

Fig 1: Neighbourhood park in a low density suburb

Fig 2: Neighbourhood park in higher density suburb

Many of these smaller parks are also used as part of local and regional urban stormwater management, where some of the park is set aside for either temporary water storage during storm events or more permanent water storage where an artificial lake is created. See photos below.

Fig 3: Neighbourhood park with a section used for temporary storage of stormwater

Fig 4: Neighbourhood park with a section used for permanent storage of stormwater

Where part of a park is set aside for either temporary water storage during storm events (photo on the left above) this part becomes unusable during that time, whereas the presence of permanent water adds to the aesthetic and natural values of the park.

In summary, neighborhood parks are small local parks that are well designed, used primarily by locals residents, have a range of facilities, often including playground equipment and are located in residential areas.

Sporting places

These are typically places where the primary use is for a specific organised sports or active activity. In Australia, it typically includes ovals used for football (AFL) and cricket, but also rectangular fields for soccer and rugby. They can be a single oval/rectangular field or have multiple fields. The sporting clubs who utilise these fields have a strong sense of ownership because participants regularly users these playing fields, and often significantly enhanced due to the presence of club rooms used for a range of social events, including during and after matches, fund raising events, annual awards nights and being hired out to the broader community for social events. See Google Earth photos below.

Fig 5: Single field sporting field

Fig 6: multi-field sporting field

Fig 7: Organised sport being played on a sport field

When the fields are not being used for organised sport, they revert to broader community places similar to neighbourhood parks but at a larger scale. However, the strong sense of ownership developed by the sporting clubs that regularly use the fields can sometimes lead to these clubs trying to exclude other people using the field(s) and facilities.

Because of the size of playing fields, many will have multi functions, for example have nature spaces or be used as part of the local or regional drainage system – see below.

Fig 8: Sporting field with a large area set aside as a nature space

Fig 9: Sporting field with a section used for temporary storage of stormwater

Outdoor skate parks and hard courts (e.g. tennis and netball) also fit in this category. Skate parks are interesting in this context in that the activity is not normally organised, and the users prefer this informality. In many cases, the sense of ownership is as significant as for playing fields which cater for organised sports.

Fig 10: Skate park in Port Macquarie in NSW

Fig 11: Skate parks in Sheffield in Tasmania

As can be seen in the Sheffield skate park, street art is often associated with skate parks, adding to the sense of place and also attracting an additional set of people who have ownership of the park.In summary, sporting places have a specific primary use which is either an organised sport or an active activity, with regular users who develop a strong sense of ownership because and , as a results strong social interactions occur in these places.

Town Squares

Town squares are often the main public places in major cities or towns where people congregate during the day, and where major events are held. They are typically located within the commercial/retail/business heart of the city, and usually there are few people who actually live nearby and who would call this place ‘local’. These places have many regular users who come from all over the city, who work in the city area. Other visitors are regular shoppers, tourists, or people who regularly/occasionally attend events held in the square. In these ways, these squares are ‘owned’ by the whole city. Below are a few examples.

Fig 12: Federation Square in Melbourne

Fig 13: Forrest Chase in Perth

These places usually have significant infrastructure to facilitate a whole range of uses and users.

Fig: 14: Chess playing in Parc des Bastions, Geneva

Fig 15: Jay Pritzker Pavilion Amphitheater in Millennium Park, Chicago

They often have significant pieces of art which invite interaction. Probably the most famous is the Bean in Millennium Park, Chicago.

Figs 16 and 17: The Bean in Millennium Park, Chicago

In summary, town squares are the main public places in major cities or towns where people congregate during the day, and where major events are held. They have many regular users, few of whom would be ‘local’, who come from all over the city, to work, shop and visit for events – they are owned by the whole city. They have significant infrastructure to facilitate a whole range of uses and users.

Coastal and foreshores nodes

Coastal areas and other foreshores, especially rivers, are linear and extends for many kilometres (many 1000’s in the case of the coast). There are often significant nodes that are highly developed with infrastructure that facilitate public activities. These nodes often develop into significant places. The less develop areas of coasts and foreshores can be considered spaces rather than places.

There is an argument that these places can be considered examples of neighbourhood parks (local beaches) and Town Squares (regional beaches). Indeed, they share many of the attributes of each of these, for example many regional beaches have facilities, infrastructure and uses which are the same as Town squares – see Scarborough Beach below.

Figs 18 and 19: Scarborough Beach in Perth WA, with facilities, infrastructure and uses the same as a town square

Two attributes differentiate beaches and foreshores from neighbourhood parks and town squares: the beach and water (ocean or river) are significant features and attracters which also allows specific aquatic uses; and, their linear nature allows for specific uses, for example walking, running and cycling, not catered for in neighbourhood parks and town squares.

Local beaches are usually located adjacent to residential areas and, as with neighbourhood parks, these places have strong senses of local ownership.

Fig 20: Falcon beach – a local beach and foreshore

Fig 21: A section of Southbank foreshore, Brisbane that is a node of community activity

Regional beaches and river foreshore nodes in large cities (Fig 21) are typically highly developed, with the adjacent area being a mix of commercial and tourist accommodation. The sense of ownership comes from both the regular local users and the regular/occasional users who are not locals but visit the place for special occasions including organised events or gatherings of families/friends.

Figs 22 and 23: to Manly beach, Sydney, and the commercial and tourist accommodation uses adjacent to the beach

Fig 24: People watching a laser show on the Brisbane River foreshore – a special event

Fig 25: Gathering of family/friends at Scarborough beach

In summary, coastal and foreshore nodes are specific highly developed locations within a broader coast or foreshore that develop significant private geography because they are either locally significant or attract people outside the local area. The attraction is for the facilities, events and the attractions associated with the water.

Streets and verges

When I am teaching and engaging with students on open space, I often pose a simple question: what are the differences between a street and a road? Whilst the volume of traffic is one difference, and a significant one, it’s the notions of localness and sense of place that are usually identified as key differences by students, where streets are seen as having a strong sense of place whereas roads act primarily as infrastructure for the transit of both vehicles and pedestrians. Sense of place develops in streets because pedestrians stop and spend time in the street, usually on the street verges and footpaths.

Streets are more likely to develop in neighbourhoods where the house is close to the path and front fences allow for a physical connection. This is less likely where there is no path and the verge merges with private property, and the resident is more likely to see the verge as private (i.e. theirs) and not public. For this reason, older suburbs are more likely to have streets and newer suburbs to have roads.

Fig 28: A typical neighbourhood street showing good connections between the house and the verge and the presence of a footpath

Fig 29: A verge in a different neighbourhood with poor connection between the house and the verge and the absence of a footpath

Community verge gardens are becoming more and more popular, and provide not only a food for locals, but also opportunities for social interactions.

Streets can be local and within a defined neighbourhood where residents meet and socialise. As well, a place is created within a town or city centre, where the footpath has been redeveloped, and often widened taking up some of the road space, and facilities are provided to encourage people and groups to gather, stop and socialise (Fig 30).

Fig 30: A widened and re-developed footpath in inner Melbourne which is now a social place

Streets and verge places are created, therefore, when people do more than just pass through. It’s when they stop and carry out public activities. As a result, a strong sense of place develops.

In some inner-city areas, the street itself becomes used for more than just cars, trucks and bikes. Traffic calming allows pedestrians to use the street, and even allow children to play – Fig 31.

Fig 31: a traffic calmed street allowing children to play

You will notice that I have not included those streets where out-door dining attached to cafes and restaurants occur. I consider these areas to be ‘acquired non-spaces’, and I will explain this in a future next blog when I get to Public non-spaces.

In summary, streets and verges places are footpaths, verges and streets where the transit of traffic and people is complimented by people stopping and socialising, often facilitated by provision of infrastructure.

Urban farms

I ummed and ahhhed about where to place Urban farms – are they public or private spaces? Certainly, many of these are on public land whereas others are on private land owned by agencies that are active in the social and community spheres – for example churches and schools. Community members are invited to both participate in the agriculture and to visit and make use of the area. The individual plots are certainly ‘owned’ by those who work them, either through a formal leasing arrangement or informally in that the individuals who work those plots are protective of them.

What I have noticed is the strong sense of place created in these urban farms. It is this strong sense of place and that these areas are, by in large, open to the broader public that makes me think these are places and not spaces.

Fig 32: A small urban farm in the middle of Melbourne’s CBD

Fig 33: A large urban farm in Portugal

In summary, urban farms are places whose primary function is urban agriculture, which facilities social interactions between the participants.

Urban nature

These are areas set aside primarily for conservation in urban areas but allow public access, either uncontrolled or controlled via fences, paths, signage etc. These aren’t nature reserves with high fences around them to keep people out: these are natural areas that are integrated into the urban fabric. Smaller pieces of urban nature in neighbourhoods become important to many locals who visit these sites and often get involved in their on-going management, often through the formation of so-called ‘friends of’ groups. In this way, these people create a strong sense of ownership of, and responsibility for, these places. This is the sense of place that emerges here.

Urban nature places can also be very large parks located within a city and not on the fringes, where the users are from all over the city. Whilst conservation is a key purpose of the park, human uses are also catered for often in special developed pockets set with a natural setting (Fig 35).

Figure 34: Small urban nature place in a suburb if Perth

Fig 35: A popular elevated walkway in Kings Park, a large mostly natural park in the center of Perth.

Whilst conservation is the primary use of the place, significant complimentary human uses is also allowed, which will inevitably compromise the conservation outcome achieved. The loss of conservation value is offset by enhanced social values.

In summary, urban nature places are areas of mostly remnant vegetation set within an urban context that are managed for conservation but allow significant complimentary human uses.

Claimed places within spaces

As noted earlier, Public Places are different from Public Spaces by having regular users who have built a sense of ownership for the place through frequent social interactions. I’ll cover the types of Public Spaces in detail in my next blog. However, specific locations within some public spaces can attract regular users and social interactions increases. These become places within spaces, or ‘claimed places”.

Two examples are shown below. Fig 36 shows the entrance to Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, which is a regular meeting place. The rest of the footpath is nothing special, and classifies as a space. Fig 37 shows public seating in a street that is an otherwise either a simple space or an acquired non-space (see the blog after the next)

Fig 36: The footpath in front of Flinders Street Station – A claimed space within a larger space (a meeting place.

Fig 37: A footpath in Brighton, Adelaide, showing a public seating areas which is a place acquired from the remaining space.

Often places are acquired when certain infrastructure is provided, especially involving cultural pieces. These places have particular meaning for certain sections of the community, or have significant broader meaning to the whole community. Fig 38 shows a section of a large foreshore reserve in Rockingham that is otherwise a space and not well used. This section is a memorial to the Australian Navy and those who have served in the Navy. Fig 39 shows a section of the Reconciliation Place part of a broader Parliamentary Zone in Canberra.

Fig 38: A section of a larger foreshore reserve dedicated to a memorial to the Australian Navy – an acquired place.

Fig 39: A section of the Reconciliation Place within broader Parliamentary Zone in Canberra – an acquired place with significant cultural meaning

Another example of an acquired place are camping grounds within large spaces like national parks – Fig 40. Many of these have many people who are regular users, and they attain a strong attachment to the place. As well, these places often have significant social interactions between the users at any time.

Fig 40: Contos camping site within the Leeuwin- Naturaliste National Park in WA.

In summary, acquired places are small section within larger spaces where, either through the provision of certain infrastructure, including cultural, or a convenient location, where people regularly gather and significant social interactions often occur.

In my next post, I will describe the types of public spaces.

Garry Middle, July 31, 2017

Types of open spaces

Overview and clarifying terminology

Terminology is important here as I have made a clear distinction between ‘place’ and ‘space’, It makes the use of the term ‘open space’ as the overall descriptor problematic. As well, the term ‘open’ is also problematic when used to describe public non-places, because they a certainly not always open to the public for use – e.g. shopping malls will have opening and closing times – and some – for example shopping malls – are enclosed and not open to the weather. So, what term should be used as the generic descriptor in this context? At this point I don’t have a simple term, so I will use the rather clumsy but accurate term ‘public places and spaces’, and avoid the temptation to make it an acronym.

The notion of ‘public’ here is not about tenure or ownership, but relates to the public being able to use a place or space, even though the access to it is controlled by a private interest.

My categories or types of places and spaces

In my first blog, I identified three broad types of places and spaces:

- A public place – which is owned publicly, has regular users who have a certain sense of ownership and private geography. Social interactions are common here;

- A public space – which is owned publicly, is frequently used by passer-byer’s who don’t really have a sense of ownership and there is a very weak sense of private geography; and

- A public non-place – which is generally privately owned, is created for people who want to use the primary service of the owner, and this space is somewhere to wait or pass through. These places have little sense of ownership by the users, and favour solitary behaviour over social interactions.

This is a very coarse categorization and not very useful, and a more detailed categorization is required. A typical approach would be to review the literature, and whilst this should provide an outcome with some academic rigour, I have adopted a more direct and observational approach. Over the past 10 or so years, when I became deeply interested in places and spaces as an academic, I have visited and photographed many examples from all over Perth (my home city), other cities in Australia, and many cities overseas as part of my travels. I have countless photographs and memories to draw on, and this is a much more interesting way to think about places and spaces rather than reading endless academic articles on the subject. My understanding of how to categorise places and spaces has been, in part, informed by my student, where, as part of my university teachings, I have got my students to think about how to categorise places and spaces. I use an exercise where I have shown students photographs of 96 different places and spaces I have visited from all over the world, and asked them to work out their own way of categorizing them. Each time I do this there are several themes that are common, but also some interesting differences and innovative ways of categorising places and spaces. The discussion below is informed by both my own observations and thinking, and the thinking of my students.

For the most part, the categories that I have come up with are primarily about a single place or space, where the whole site functions as a single type. Large places and spaces can be heterogeneous and not fit a single type, especially large public places.

The diagram below shows categories I have come up with.

The next three blogs will give more details of each category based on the three broad types.

Introduction

I’ve been doing research into public open space for several years now, mostly into active open space – i.e. active sporting fields. (if you would like to read about this research in more detail you can go to the relevant page of my website – click here for the link).

More recently, I’ve become interested in the broader topic of open space planning. This blog will allow me to explore the issues and ideas around this topic.

Firstly, I should explore what is meant, and covered, by the term ‘public places and spaces’?

The word ‘public’ does not refer to ownership – i.e. I am not just referring to what has been typicallycalled ‘pubic open space’ – i.e. reserve owned and managed by governments. “Public’ means spaces and places that are accessed by the public, and whilst this will mostly be ‘pubic open space’ – neighbourhood parks, playing fields, conservation reserves, coastal & river foreshore etc – it also refers to privately owned spaces – for example shopping centres/malls.

At this point, it is worth digressing to discuss the difference between these two notions of publicly owned and privately owned places and spaces, and also to draw some distinction between spaces and places. To this end, I will refer to Marc Auge’s essay called Non-places: An introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (translated by John Howe).

First the notion of place. Auge says this of ‘place’ –

… a place: the one occupied by the indigenous inhabitants who live in it, cultivate it, defend it, mark its strong points and keep its frontiers under surveillance, but who also detect in it traces of … ancestors or spirits which populate and animate its private geography … (P42)

Whilst it is clear that Auge is referring to a broader notion of place – i.e. where one lives – this idea fits well with the notion of public places as used in this discussion. Here, the “indigenous inhabitants” are the regular users of then place, who have a sense of ownership and responsibility for it and a certain sense of “private geography” will emerge. This strong sense of belonging can only (or perhaps is most likely to) occur if the place is in public ownership. As well, these places are locations where the activities carried out there are the purpose for the place’s existence. This is a significant point – i.e. a public place is about what goes on there. This is quite different from what Auge calls ‘non-places’

Non-places have three characteristics. First, they have a specific purpose or provide a specific service in relation to a different and private function – for example a transit lounge at an airport, a train station, a shopping mall. People don’t choose to go to these places, but visit them because of some other purpose. The private owner decides to create these places because they want their customers to enjoy the overall experience of the primary service – travelling, hoping etc. Second, inter-personal contact is likely to be superficial and in-passing, which tends to favour solidarity rather than socialising. People in those places are merely waiting for the primary service to begin. Third, these places have much stronger “instructions for use” (p96), especially prohibitions. There is a greater sense that the owner is in-charge of things rather than the user – the recent moves by Qantas to improve the dress code in the Qantas club lounges is an example – see this link. In general, then, ‘non-places’ are privately owned and allow the public to wait for the primary service to become available.

So, how is a space different from a place?

Auge uses the term ‘space’ in land use planning sense as what we was humans create as part of city building. It can refer to open space but also to more person items like houses, rooms, offices etc. Spaces are the more concrete things that define a space/place – structures like walls, fences, play equipment and the area that defines the space’s dimensions, location and characteristics.

I’ll now turn to the use of ‘space’ in the ‘open space’ context. A ‘space’, with its emphasis on what physically defines it, is less “occupied by the indigenous inhabitants” than a place, with a weaker sense of belonging felt by its users. It is somewhere between a place and a non-place: it is a publicly owned asset freely available to the public, but with a much weaker sense of ‘private geography’. A footpath and a large city square best meet that definition.

So, we have three broad types of ‘public places and spaces:

A public place – which is owned publicly, has regular users who have a certain sense of ownership and private geography. Social interactions are common here;

A public space – which is owned publicly, is frequently used by passer-byer’s who don’t really have a sense of ownership and there is a very weak sense of private geography;

A public non-place – which is generally privately owned, is created for people who want to use the primary service of the owner and this space somewhere to wait or pass through. These places have little sense of ownership by the users, and favour solitary behaviour over social interactions.

In my next blog, I will discuss these three broad types in more detail.